Artificial intelligence has To date, he has been tuned into cultural circles as a Bogeyman: Software will take the work of writers and translators, and AI-generated images impede the death toll for illustrators and graphic designers.

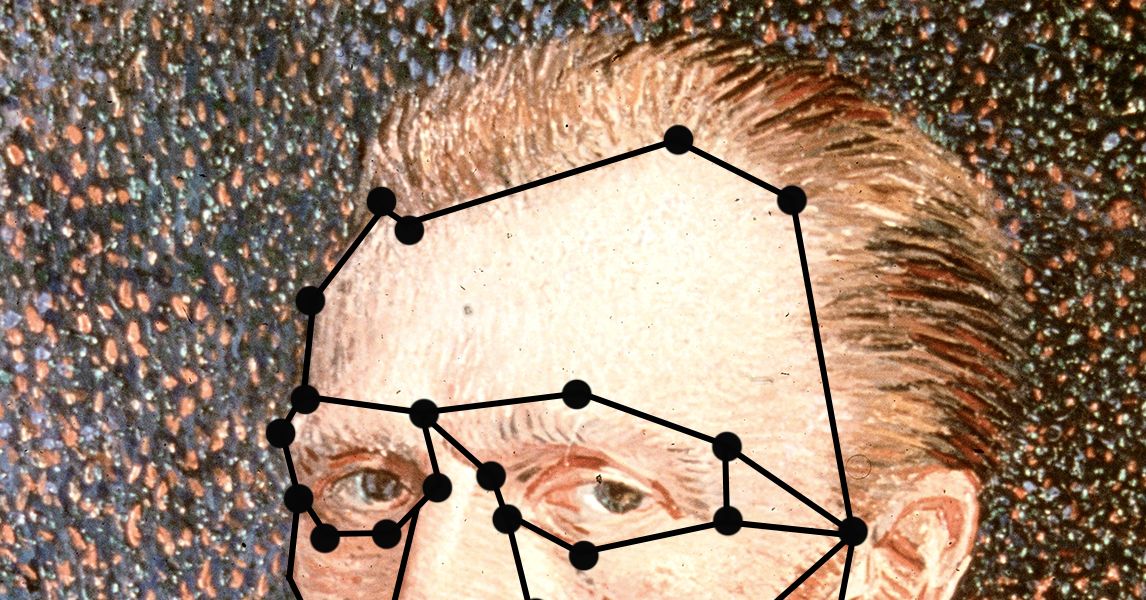

Yet there is an angle of a high culture where AI takes on a lead role as a hero, and not displaces the traditional protagonists – art experts and conservators, but adds a powerful, compelling weapon to their arsenal when it comes to fighting for falsifications and abuse. AI is already exceptionally good at recognizing and verifying an artist’s work based on the analysis of a digital image of a painting alone.

AI’s objective analysis threw a wrench in this traditional hierarchy. If an algorithm can determine the authorship of a artwork with statistical probability, where does it leave the old art historians whose reputation is built on their subjective expertise? In fact, AI will never replace gourmets, just like using X-rays and carbon dates decades ago. It is simply the latest in a series of high-tech instruments to help with verification.

A good AI must be fed a composite data set by human art historians to build his knowledge of an artist’s style, and human art historians must interpret the results. This was the case in November 2024, when a leading AI firm, art recognition, published his analysis of Rembrandt’s The Polish rider– A paint that confuses famous scholars and led to many arguments about how much, if something, was actually painted by Rembrandt himself. The AI exactly matched what most experts posted about which parts of the painting by the Master, who were by students of him, and what the hand of over-enthusiastic repairers entailed. This is especially compelling when the scientific approach confirms the knowledgeable opinion.

Our people find hard scientific data more compelling than personal opinion, even if the opinion comes from someone who is an expert. The so-called “CSI effect” describes how jurors consider DNA evidence as more persuasive than even evidence evidence. But when expert opinion (the eyewitnesses), origin and scientific tests (the CSI) all agree on the same conclusion? It is as close to a definite answer as one can get.

But what happens if the owner of a work that at first glance seems completely unpleasant to the point of being laughable, a smooth firm recruiting with the task of collecting forensic evidence to support a preferred attribute?

Lost and found

In 2016, an oil painting arrives at a flea market in Minnesota and was bought for less than $ 50. Now its owners suggest that it could be a lost of Gogh, and that it would be worth millions. (One estimate indicates $ 15 million.) The answer – at least for everyone with functioning eyeballs and a passing familiarity with art history – was a resounding ‘nah’. The painting is stiff, clumsy, completely missing from the feverish impasto and rhythmic brushing that defines the Dutch artist’s oeuvre. Even worse, it carried a signature: Elimar. And yet this questionable painting has become the center of a struggle for authenticity, one in which scientific analysis, market forces and wishful thinking clash.

The owners of the ‘Elimar van Gogh’, as harmed in art circles, are now an art consulting group called LMI International. They invest a lot in getting experts to say what they want to hear: that it is in fact a sincere Van Gogh. This is where things get dark. The world of art verification is not a simple matter. Unlike the hard sciences, art history deals with probabilities, gourmets and competitive expert opinions. It is also of great importance, an industry driven by financial incentives. If the painting is really considered, its value is. If it is considered a false, or rather in this case a derivative job of someone named Elimar who put a bit on canvas, maybe it was inspired by Van Gogh at the time, but with none of his talents, it is virtually worthless – about as valuable as you would expect to find a flea market in Minnesota for under 50. This imbalance in interests has led to a dangerous tendency: to hire experts not to determine authenticity, but to confirm it.